One of my favorite stories is that of the Christmas Truce of 1914. Stanley Weintraub, author of Silent Night: the Remarkable 1914 Christmas Truce wrote about the event more briefly in The Christmas truce: When the guns fell silent Independent 12/24/05. A fairly recent French film has been made about it, called Joyeux Noël, which I hope will make it to American theaters one day.

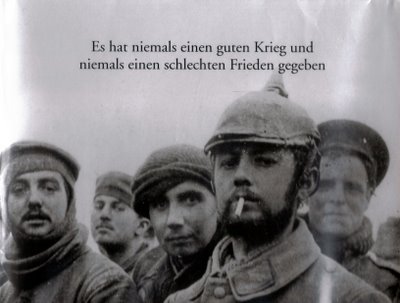

One of my favorite stories is that of the Christmas Truce of 1914. Stanley Weintraub, author of Silent Night: the Remarkable 1914 Christmas Truce wrote about the event more briefly in The Christmas truce: When the guns fell silent Independent 12/24/05. A fairly recent French film has been made about it, called Joyeux Noël, which I hope will make it to American theaters one day.The photo above is part of the back cover of Der kleine Frieden im Grossen Krieg [The Little Peace in the Great War] (2003) by Michael Jürgs. The caption says, "There has never been a good war and never a bad peace."

While most of us could think of a war we considered good in some way and likewise a peace that was less than good, the sentiment is a basically sound one.

Describing the Christmas Truce, Weintraub writes:

By Christmas morning, no man's land between the trenches was filled with fraternising soldiers, sharing rations, trading gifts, singing, and - more solemnly - burying the dead between the lines. (Earlier, the bodies had been too dangerous to retrieve.) The roughly cleared space suggested to the more imaginative among them a football pitch. Kickabouts began, mostly with balls improvised from stuffed caps and other gear, the players oblivious of their greatcoats and boots. The official war diary of the 133rd Saxon Regiment says "Tommy and Fritz" used a real ball, furnished by a provident Scot. "This developed into a regulation football match with caps casually laid out as goals. The frozen ground was no great matter. Das Spiel endete 3:2 fur Fritz." Other accounts, mostly German, give other scores, and British letters and memories fill in more details.And he laments:

A Christmas truce seems in our new century an impossible dream from a more simple, vanished world. Peace is indeed, even briefly, harder to make than war.

William Faulkner projected the Christmas Truce on a much larger scale in his novel A Fable (1954). (English professors seem to think it's not technically a novel but literally a fable but don't ask me to explain the difference.) This 1968 Signet paperback edition pictured the protagonist as a Christ figure, and Faulkner indeed uses Christian symbolism heavily in the novel/story/fable:

For some reason, Faulkner wrote part of this book on the wallpaper in one of the rooms of his small mansion in Oxford, MS, Rowan Oak. You can still see it there.

Tags: christmas truce of 1914, first world war

No comments:

Post a Comment