I've seen the monthly magazine Current History for, well, as long as I remember. When I was in highl school, I can remember occasionally stumbling across it when doing research papers like, "Two Interesting Facts About Ecuador". Generally, it seemed to be the blandest, most sleep-iducing publication you could find unless you got your jollies from read about bauxite exports.

So, I don't know of they went through some transfiguration, or if the scales fell from my eyes, or maybe I was too distracted those days by raging hormones. But now that Borders and Barnes & Noble - and Cody's in the San Francisco Bay Area - regularly put magazines in front of our faces that were once found only in musty corners of libraries, I find myself checking out what's in every issue. And it has some pretty darn good stuff.

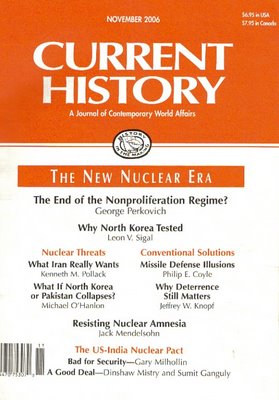

The November 2006 issue is devoted to the theme "The New Nuclear Era". The lead article, "The End of the Nonproliferation Regime?" has George Perkovich of the Carnegie Endowment explaning how vital the existing international nuclear-nonproliferation arrangements are and why they should be strengthened, not destroyed as the Cheney-Bush administration has tried to do:

The nuclear nonproliferation regime is actually one of history's greatest success stories. Attempting to keep the vast majority of nations from acquiring the most potent technology on earth, while establishing rules under which a small minority manage these technologies, the nonproliferation system has been "defeated" by only one country that acquired nuclear weapons illegally: North Korea. The system is being tested by another, Iran, and has been bypassed by three others: Israel, India, and Pakistan. Although much of the world would say the system is flawed insofar as the states with nuclear weapons are not pursuing disarmament seriously enough, this disaffection does not necessarily portend a collapse of the regime. ...

The sole superpower cannot solve the North Korean and Iranian cases, or change the rules regulating nuclear technology. It must find ways to induce other key powers to cooperate with it even as they also wish to balance, influence, and perhaps reduce America's power. This is what statesmen do, and nonproliferation is a problem of statesmanship more than it is of military power.

Kenneth Pollack, whose credibility has been seriously damaged by his role as a leading "liberal hawk" advocate for invading Iraq, writes about "Bringing Iran to the Bargaining Table". Taking Pollack with appropriate critical reservations, he does make a couple of important and credible points. One is that there does seem to have been a significant division in the Iranian leadership over their nuclear program and their willingness to negotiate ovr it. He also cities some previous examples of various states that at one point intended or attempted to develop nuclear weapons programs and then gave them up:

In the 1960s it was considered a foregone conclusion that Egypt would develop a nuclear weapon. Indeed, that nation's strategic and psychological incentives were even more compelling than Iran's are today. Egypt was locked in a conflict with a nuclear-armed Israel that resulted in four mostly disastrous wars (for Egypt) in 25 years, and Cairo aspired to be the "leader of the Arab world." Yet Egypt shut down its nuclear weapons program entirely of its own volition because the leadership in Cairo concluded that it had higher priorities that the pursuit of nuclear weapons was undermining.

Italy, Australia, Sweden, Japan, and South Korea considered developing nuclear weapons at various times, and the Italians and Australians actually made considerable progress toward that goal. However, all of them decided that nuclear arms would be counterproductive in relation to other, higher priorities, and that they could find ways to deal with their security problems (including even South Korea) through other means.

In the early 1990s, Belarus, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan went even further, voluntarily surrendering the nuclear arsenals they had inherited from the Soviet Union. Although many Western academic strategists believed that they were insane to do so, all three recognized that the security benefits from possessing nuclear weapons were outweighed by the diplomatic and economic benefits of giving them up. Strong economies and good relations with the rest of the world were of far greater importance to them.

The Brookings Institute's Michael O'Hanlon lookos at the important question of particular concern now with respect to Pakistan and North Korea, "What If a Nuclear-Armed State Collapses?" It's not a pretty prospect. The only real solution is effective international nonproliferation agreements, preferably with Pakistan and North Korea giving up their nukes. Of course, Pakistan will not give up its nukes as long as India has them and the dispute over Kashmir remains unresolved. Reliance on military options in which other nations would seize or eliminate their nukes in the case of governmental collapse is a highly uncertain safeguard.

Former SALT negotiator Jack Mendelsohn writes on "The New Threat: Nuclear Amnesia, Nuclear Legitimacy". It's still insufficiently appreciated how much the Bush Doctrine relies on an underlying belief in the usability of nuclear weapons and the general invicibility of the United States military. The dynamimcs of the nuclear arms race clearly show that, despite the perpetual nuclear wet-dreams of our Dr. Strangeloves, an increasing reliance on nuclear weapons produces a decrease in security, especially for the United States:

Nuclear weapons are a clear and present danger, especially to the United States. Because Washington is at present unwilling to negotiate treaties or enter into binding agreements, the burden of securing the nation's future while advancing global security will fall on the next president. If his (or her) administration hopes to enhance us security against the most serious threats, it will have to do more than pursue terrorists or enforce nonprohieration. It will also have to reduce the attractiveness of nuclear weapons to the United States and to the rest of the world. This entails adopting policies that delegiti-mize nuclear weapons by reducing the incentives to acquire them and by relegating them to a deterrent or retaliatory role or to weapons of last resort.

If Americans fail to wean themselves from the idea that the threat or use of nuclear weapons can ensure their security, they are likely to find that the cure for nuclear amnesia involves a nasty shock and an acrid smell.

Jeffrey Knopf of the Naval Postgraduate School reinforces that argument by pointing out the danger of the Bush Doctrine's reliance on "preemption" in "Deterrance or Preemption?" It's always important to remember, though, that the Bush Doctrine in Iraq has meant the use of preventive war, which has an established meaning in international law that is qualitatively different from preemptive war.

Other articles in this issue include Philip Coyle of the Center for Defense Information on the "missile defense" boodoggle, the most glaring examply today of an often-dysfunctional military-industrial complext; a look at the implications of North Korean nuclear testing; and, two views of the recently-approved US-India nuclear agreement.

Today's Republican Party is largely committed to promoting nuclear proliferation rather than restraining it. They reserve the rhetoric of nonproliferation mainly for an excuse to attack whatever country is at the top of their hit list. As Perkovich notes with particular reference to banning nuclear tests, this can result in very negative consequences for the world:

US opposition to the test ban is almost entirely confined to the Republican Party, and may be a legacy of opposition to the Clinton administration. The United States has followed a moratorium on nuclear testing since 1992, and the Bush administration, after six years, remains pledged not to conduct nuclear tests. If the United States were to resume nuclear weapon testing, it is nearly certain that Russia, China, India, and Pakistan would quickly follow suit. India and Pakistan would focus on developing and proving thermonuclear weapon capabilities, which would greatly increase the destructiveness of their arsenals. In such a dramatically "nuclearized" global environment, political forces in Japan and South Korea would demand that their governments reconsider their commitments to shun nuclear weapons. Iran could point to its north, east, and west and exclaim that rising nuclear threats justify its interest in a full-service nuclear program.Tags: nonproliferation, nuclear weapons, nuclear nonproliferation

No comments:

Post a Comment