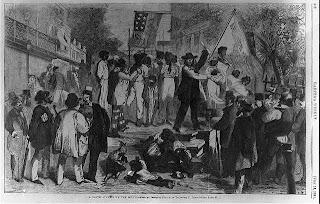

Slave auction (from Harper's Weekly 07/14/1861)

Returning again to the Southern Agriculturist of Charleston, South Carolina, we find an article in the November 1836 edition by "A Planter", offering a picture of a well-run plantation. Big parts of this one read like pure propaganda: the tender care lavished upon slave children, the encouragement for slaves to follow their marriage vows. Slave children were actually typically provided minimal care, if that. Marriage vows had no legal force among slaves. And planters often found no difficulty in forcing violations of them, and generally little compunction about splitting families in the sale of slaves.

Even the cheery propaganda, though, can't entirely hide the ugly sides of the Peculiar Institution:

I have a nurse appointed to superintend all my little negroes, and a nursery built for them. If they are left to be protected by their parents, they will most assuredly be neglected. I have known parents take out an allowance for their children, and actually steal it from, them, to purchase articles at some shop. Besides, when they would be honest to their offspring, from their other occupations, they have not the time to attend to them properly. The children get their food irregularly, and when they do get it, it is only half done. They are suffered [i.e., made to suffer], by not having one to attend to them, to expose themselves; and hence many of the deaths which occur on our plantation.In other words, in the ideal patriarchal plantation, slave parents have no right at all over the upbringing of their children. And besides, the slaveowners give them too much work to be able to take care of their children anyway.

The part about babies dying from exposure, presumably from heat in the fields or slave houses while their parents are working, paints an especially grim picture of life and death under slavery. Oddly, in the same paragraph where our Planter claims to provide tender loving care to slave children away from their parents - "I have a nurse appointed to superintend all my little negroes" - they still have many deaths of children by exposure. And this in an article bragging about the wonderfulness of life on the plantation.

Let's be fair to our author, A Planter. Since it was not uncommon for slaveowners to father children from their slaves, some of the wards allegedly being cared for in thee nursery may be biological children of A Planter. So it's not entirely fair to say that all these children are denied their parents' care.

Our Planter argues, "Cleanliness is a matter which cannot be too closely attended to." Now, some portion of this talk about cleanliness among the slaves, which was referenced in yesterday's quotes from Southern Agriculturist, was surely propaganda. The slaves' work in the field was scarcely free from untidy conditions. And the truth is that, despite the ideological claims to the contrary, owners weren't always overly solicitous about the health of their human property.

But even if we take the follow account as Gospel truth, think about what this says about the absolute power of the masters over the slaves, and how it visibly deprives all the adult slaves of dignity in front of all the others, including the children:

I appoint a certain hour for attending to this matter on each Sabbath, say nine o'clock in the morning. Every negro distinctly understands, that at this hour he will be reviewed. An hour or so previous to the review, I make it the business of the driver to sound the horn, for the negroes to prepare themselves and houses for inspection. When the hour for review has arrived, it is also his business to attend upon me, and report the plantation ready for inspection. This being done, I repair to the negro houses. At the door, of each house, the occupants thereof are seen standing with their children, if they have any. My business here is to call their respective names, and to see that every one has had his head well combed and cleaned, and their faces, hands and feet well washed. The men are required, in addition to this, to have themselves shaved. That they may have no excuse for neglecting this requirement, those that need them are provided with combs and razors. I now see that their blankets, and all other body and bed clothing, have been hung out to air, if the weather be fine. Their pots are also examined. I particularly see "that they have been well cleaned, and that nothing like "caked hominy" or potatoes is suffered to remain about them. I next enter their houses, and there see that every thing has been cleansed - that their pails, dressers, tables, &c. have all been washed down - that their chimneys have been swept and the ashes there from removed to one general heap in the yard, which serves me as an excellent manure for my lands. Being situated where my negroes procure many oysters, I make them save the shells, which they place in one pile, of which I burn lime enough each year, to white-wash my negro houses; both outside and inside. This not only gives a neat appearance to the houses, but preserves the boards of the same, and destroys all vermin which might infest them. From the inspection of the negro houses, I proceed to their well, and there see, that the water is pure and healthy. [my emphasis in bold]An earlier piece in the February 1836 edition, this one actually signed with a name, B. Herbemont, "On the Moral Discpline and Treatment of Slaves", offers considerations about other aspects of slave control. Interestingly enough, he states, "I have reason to conclude, that there are very few planters who have any thing like a regular system for either the moral or physical government of their slaves." Since at a very basic level, slavery was very much about the "physical government" of the human chattel, it's an odd statement on its face. But it also is difficult to reconcile while the ideological image of patriarchal masters tenderly concerned for the well-being of their slaves.

He gives an example of how one slaveowner solved a problem:

He tells me that when he commenced planting, a few years since, he found the plantation which he had inherited from his father, and to which he had added very considerably, both in land and negroes, in an exceedingly disordered state; or, to use his own strong expression; "found it a wreck in every way." He found his negroes, to all appearance, devout religionists. Their practice was to congregate twice a week, besides Sunday mornings. From the inquiries he made of his overseers and neighbours, he had many reasons to believe, that no good arose from this course: but on the contrary, that all the most zealous pretenders to religion were the greatest rogues. He attended several of their meetings, and from their most absurd perversions of the scriptures, and the monstrous absurdities which they uttered, with the most sactimonious countenance, he was most fully satisfied that no morality could proceed from these meetings. He afterwards found that they committed depredations of all kinds, killing his beeves, hogs and sheep, thrashing his rice in the woods, breaking corn and grubbing his potatoes. He ascertained by the fullest and clearest proofs, that the coloured preachers were the greatest and most active thieves. He also found that among the women, those who had the most pretensions to religion, were nearly all implicated in the misdeeds. He was, therefore, induced to break up all their religious meetings, and to make examples by severe punishment on the most guilty ones. Punishment also followed any violation of his new regulations. He then resorted to a very different course, and adopted a system calculated to produce cheerfulness, and keep them in good humour as much as possible. Being determined that there should be no fault on his part, he fed and clothed them well, and induced them to occasional meetings for the purposes of meriment [sic]. He had fiddles and drums for their use, promoted dancing, and he found that by punishing certainly, though moderately, all ascertained delinquencies, they became much better tempered, and certainly much more honest.He commends instead the example of "[t]hose gentlemen at the South who have hired white persons to preach to their slaves every Sunday". But he recommends to built upon the fact that blacks "are naturally prone to gaiety" by encouraging various recreational activities. He doesn't specify encouraging them to get drunk during their scant time off from work. But that was commonly done, and done consciously as a means of distracting slaves from activities potentially less wholesome for slaveonwers' interests. Herbemont cites historical precedent for this recommendation:

There never was, perhaps, a more happy, contented, honest, religious and moral people than the peasantry of the continent of Europe. I speak more particularly of the peasantry of France before the revolution. Their habitual cheerfulness and the good feelings which it promotes, were most probably the chief cause of it.The oddities that appear in proslavery advocacy writing makes you wonder if such pleas had become so ritualized that a writer could expect the readers not to notice when they didn't even make sense. Here he holds up the example of the happy French peasantry "before the revolution". Uh, dude, that's a pretty big qualification, isn't it? And might it not suggest that peasants' apparent contentment at their recreational activities may not express their entire attitude toward the social order under which they live?

As from these proslavery articles directed at a slaveowning audience, neither the houses, nor their children, nor their recreations, nor their souls - and certainly not the bodies - of slaves were free from dictation by the master and the overseer.

Tags: confederate heritage month 2009, slavery

No comments:

Post a Comment