Peace and Love poster, 1968

Peace and Love poster, 1968Since the elections a few weeks ago, we've seen the Republican "culture warriors" falling back on some of their most primitive concepts derived from some Spiro Agnew version of "the 60s" filtered through the Oxycontin haze of Rush Limbaugh and the other worthies of hate radio blessed by the benedictions of the Christian dominionists in which "hippies" and antiwar protesters and, you know, rowdy minorities are the root of all social evil. And all foreign policy failures and the lost wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, of course.

It got me to thinking a bit about what there was in the social movement known as the "hippies", the real existing hippies that is, not the bizarre imaginary construct in the minds of the Christian Right "culture warriors", that may have been substantial and important.

It's not just that, though. When I was on vacation in Austria this past summer, I went to an exhibition of psychedelic art in the Museum Quartier in Vienna. It focused on art of that type from the late 1960s from four cities: San Francisco (of course!), London, Frankfurt and Hamburg. It included some short films with sounds tracks of snatches of urban sounds. I actually had a moment of revelation, not with flashing bursts of colored lights or anything, when I was watching one of those. It occurred to me that this is the sort of art that Yoko Ono was doing, and I thought, "Oh, this is what they were doing on 'Revolution #9'". That was a very unusual track on the Beatles White Album from 1968 that has tended to strike most Beatles fans then and sense as a bunch of random sounds. Authorship is credited to John Lennon and Paul McCartney. But it was Yoko Ono piece.

I haven't actually gone back and listened to "Revolution #9" since then. It's too satisfying to think I finally "get it" to risk actually listening to it and realize that maybe I still don't get it.

I was struck with the visual art in that exhibit by how so much of it emphasized harmony, flow and tranquility. Not in the propaganda sense of slogans saying "peace is good" but in the tone of the pictures themselves. The first poster I saw going into the exhibit made a good impression on me though it was one of the few scenes depicting some kind of violence. It was a psychedelic movie poster showing Klaus Kinski as a gangster holding a machine gun. The late German actor Kinski produced one of the true natural phenomena of his time, his daughter Nastassja Kinski. She looks amazingly like him, but she's gorgeous and he was ugly as sin (at least in many of his movie roles).

"Hippies" were a group that can't be defined with any great precision. You can construct a profile of, say, Chamber of Commerce memebers or of who voted for Richard Nixon in 1968. But the hippie movement or phenemenon was a diverse and informal social trend from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s or so. It was identified with colorful, loose clothing, rock music festivals, long hair for both men and women, beards, recreational drug usage, pacifism, relaxed attitudes about sex. The idea of getting "back to the land" by living in the country and growing your own food was part of the hippie subculture. Meditation and "eastern religions" (Buddhism, Hinduism) played their part. Broadly speaking, there was a sense of wanting to create alternative lifestyles outside the available conventional options, in terms of both work and personal relationships. The hippies were predominantly people in their teens and twenties.

It's worth remembering as well what the hippies were not. While it's hard to draw rigid lines, the civil rights activists and antiwar activists were not hippies, while hippies were often apolitical, seeing politics as irrelevant to their lives or as a corrupt part of the established society. The hippies were mostly whites. And while kids from genuinely poverty-stricken families weren't so attracted to the hippies, the Republican culture-war stereotype that they were a bunch of spoiled rich kids is also not a meaningful picture. If a meaninglu demographic breakdown could be compiled on them, I would expect that white-collar workingclass and professional families would be heavily over-represented among them compared to other groups.

And because we're dealing with a vaguely-defined social trend, it's also fairly hard to say what its lasting contributions have been. The art and music, for one thing, have proven to be durable, as that exhibition reminded me. It shouldn't be difficult to trace important elements of today's popularity of organic food at least in part to the hippies. Certainly they gave a boost to environmental consciousness, though Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir came along way too early to be hippies. Certainly, the kind of respect for nature shown by writers like Muir and Henry David Thoreau resonated with many who were attracted to the hippie lifestyle(s).

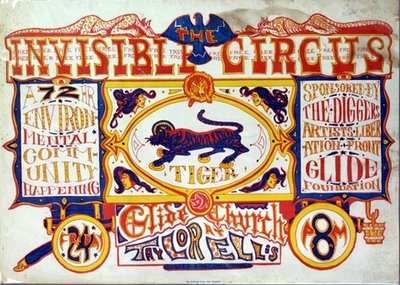

Advertisement for an environmental "happening" in San Francisco, 1967

Advertisement for an environmental "happening" in San Francisco, 1967It would be tempting see elements of feminism and multiculturalism in the hippie movement. But it's hard to see it as being a direct predecessor of major contributor to those movements. The hippies did raise questions about established family norms, especially those who built communal living arrangements. But family structures and gender roles aren't so easily challenged as a movement with a "let it be" attitude was inclined to do. And although the hippies certainly sympathized with many of the goals of the civil rights movement and were willing to borrow from African-American culture, they tended to be non-political. And most of them were white. It just seems to me that the hippie movement's contribution specifically to the multicultural consciousness was limited and indirect.

Psychedelic art and drugs were more likely to get mass-media coverage in those days than gay and lesbian issues. The hippies' willingness to challenge existing assumptions about sex and family life surely contributed to greater tolerance and awareness of homosexualtiy. But it's hard to say how much.

There were clearly some negative aspects of the hippie movement, as well. Drug abuse problems would quickly come to mind for most people. And rightly so. Marijuana for some reason that has always been hard for me to understand came to symbolize the horrors of, I'm not quite sure what - Otherness, maybe - for nice conservative white people. But some of the harder drugs that also became part of the hippie scene, including psychedelics like LSD and psyloscibin, were more dangerous, both in terms of unpredictable effects on individuals and also in the danger of overdoses, because quantities were harder to measure and the drugs were often "cut" with others, like amphetamines. On the whole, I would find it hard to identify anything terribly socially constructive about the role the hippie movement played in promoting the increased use of recreational drugs. We should also remember, though, that hippies were by no means the only people around who used recreational drugs. There were plenty of "straights" (at the time the word meant non-hippies), even more conservative ones, who shared that habit with the hippies.

And, in general, as I've often noticed with regret, some people are unconventional because they have some substantial reason to reject the conventional. Others are unconventional because they just can't hack it to meant conventional expectations, or because they are lazy, or because they are disturbed in some way. Jackson's Browne's old song "Before the Deluge" refers to the hippies of those times:

Some of them were dreamers

And some of them were fools

And for some of them

It was only the moment that mattered

Hippies and the "culture warriors"

In some ways, the vague notion of "hippies" became sort of a culture-war Rohrschact test in which the "straights" used them as a blank slate to project their own dislikes onto. And that still goes on with the Republican culture warriors. How one looks at their effect on current religious ideas and practices is a good example. The hippies helped popularize "eastern religions", a term I put in quotation marks here because that is a buzzword in the usage of many Christian evangelicals for a set of evil, deluded religions that send people to Hail. More awareness and openness to Buddhism and Hinduism may seem like a positive thing to us ecumenical Christians. I would point out the cult offshoots of that openness as a negative factor. But if you think "eastern religions" are just evil, there's nothing positive about that aspect of the hippie movement at all.

Former Los Angeles Times reporter Russell Chandler described the influence of the hippies on the later New Age/esoteric advocates and believers in his 1993 book Understanding the New Age. He actually provides a decent, informed, fair description of New Age beliefs. But he also makes it clear in this book, which was published by the Christian publishing house Zondervan, that he considers himself an evangelical Christian who, among other things, worries about people getting infected with demons. But this is a good brief summary:

Contemporary roots of the New Age can be found in the counterculture movement of recent decades. The beatniks of the 1950s were fascinated with Zen; a decade later came the hippies "with their acid dreams and Eastern gurus, their flower power and Utopian radicalism," wrote Brooks Alexander. "Next in line was the 'human potential movement' of the 1970s, spearheaded by 'humanistic' therapists of various mystical inclinations. Esalen was the touchy-feely Mecca for the upscale, post-hippie seeker. In the 1980s, all these strands and more came together, mingling in new, fanciful ways."Cover to Timothy Leary, Psychedelic Prayers After The Tao Te Ching (1966)

Gordon Melton pinpoints 1971 as the galvanization date for the movement in America. It was the year that the national periodical, East-West Journal, was first published, as well as the first representative book, Be Here Now, written by Baba Ram Dass, the Jewish-born Richard Alpert. A former psychology professor, he and colleague Timothy Leary—both were fired from Harvard—extolled "psychedelic mysticism" produced by using LSD and other hallucinogenic drugs.

Alpert, finding his personal guru in India, reemerged as Ram Dass and "preached a new, hybrid message of spiritual ecstasy and 'newness,' which he committed to print as a crazy pastiche of bold-face words strewn all over the pages in scissors-and-paste fashion," described [Carl] Raschke.

Meanwhile, Carlos Castaneda's books about his Mexico desert adventures with a bizarre Yaqui Indian sorcerer, Don Juan, "sold millions of copies and ... attracted many who followed his path of initiation through the experience of hallucinogenic mushrooms."

Again, this is a non-threatening description of a process to most people. To the devout Christian culture warrior, it's the history of a sinister, even Satanic development.

Again, this is a non-threatening description of a process to most people. To the devout Christian culture warrior, it's the history of a sinister, even Satanic development.It's also important that today's Christian culture-warrior image of "hippies" is merged with other images of the Other to yield the contempt they still express for what Jane Hamsher and Duncan Black ironically call "dirty [Cheney]ing hippies". Vice President Spiro Agnew was the most prominent promoter of this notion for the Nixon administration before he had to resign in disgrace over a bribery scandal. But Ronald Reagan was one of the first major politicians to see the potential of such negative images of hippies to mobilize some of the darker fears and prejudices of white voters during his successful gubernatorial campaign of 1966.

For some background, California in some ways was ahead of the curve in some of the social developments of the 1960s. Student demonstrations at Berkeley in particular shook people up. And in 1965 was the large Watts riot in Los Angeles, which was both a symptom of racial tensions and a contributor to racial fears and hatreds in the aftermath. The famous Summer of Love which was in many ways the high point of the hippie phenemenon was still to come. But hippies and the term hippies (derived from an early Norman Mailer coinage, "hipster") were well known by then.

Jules Tygiel in his contribution to the collection What's Going On? (2004), "Reagan and the Triumph of Conservatism" gives a flavor for how Reagan spun the tale. And Reagan did have a talent for creating memorable images, however regretable some of the causes in which he employed them may have been:

Vietnam and the offshoots of the antiwar agitation also had overtones in Reagan's most potent statewide issue. Even before he had announced his candidacy and before professional pollsters had detected it, Reagan had discovered that wherever he spoke "this university thing comes up" [meaning student protesters]. People repeatedly asked him about "the mess at Berkeley." In his announcement speech in January 1966 Reagan had raised this issue with rhetorical vehemence. "Will we meet [the students'] neurotic vulgarities with vacillation and weakness," he asked, "or will we tell those entrusted with administering the university we expect them to enforce a code based on decency, common sense, and dedication to the high and noble purpose of the university?"" Throughout the campaign, Reagan returned to this issue. "There is a leadership gap, and a morality and decency gap in Sacramento," he exclaimed, which had made it possible for "a small minority of beatniks, radicals and filthy speech advocates" to bring "shame to ... a great university."As Tygiel mentions in the quote below, Reagan's 1966 campaign was very much focused on white voters. He wasn't interested in trying to identify with the wing of the Republican party who supported civil rights legislation, which included very many sitting Republican Congress members and Senators on the key civil rights legislation of 1964 and 1965. So when he talked about the Tarzan, Jane and Cheetah (Tarzan's chimpanzee companion), he expected his white audience to relate the allusions to jungle imagery and bad smell to others than young white hippies. Tygiel continues:

As Matthew Dalleck has written, the issue of morality, as exemplified by Berkeley radicals, became "a convenient catchall, an umbrella that allowed [Reagan] to weave together an effective and articulate assault on everything that happened in the state during [encumbent Goverernor Pat] Brown's tenure." Reagan decried hippies as people who "act like Tarzan, look like Jane, and smell like Cheetah." He attacked the rise of welfare costs, asserting that working people had been "asked to carry the additional burden of a segment of society capable of caring for itself," but that preferred to make welfare "a way of life, freeloading at the expense of more conscientious citizens." (my emphasis)

Reagan managed to merge the antiwar and morality issues in a May 12 speech in which he excoriated the conduct of participants at a Vietnam Day Committee dance on the Berkeley campus. He characterized the goings-on as "so bad, so contrary to our standards of decent human behavior, that I cannot recite them to you from this platform in detail." Nonetheless, he described "nude torsos ... twist[ing] and gyrat[ing] in provocative and sensual fashion," blatant sexual misconduct, and the omnipresent smell of marijuana. University and county officials dismissed Reagan's allegations as exaggerations, but the charges rang true [for many white voters], and Reagan's disgust accurately reflected the sentiments of many of his fellow Californians.What Reagan accomplished in 1966 was to build a coalition with the support of many white Californians who came to see themselves the way many whites in segregated Deep South states long before the hippies or the beatniks came on the scene. As Tygiel writes:, "Reagan's rhetoric encouraged a culture of victimhood among the affluent white majority, wherein unsung working people paid 'exorbitant taxes to make possible compassion for the less fortunate,' having 'to sacrifice many of their own desires and dreams and hopes' in the process".

The growing volume of Black Power voices gave Reagan additional ammunition. An inflammatory appearance by militant firebrand Stokely Carmichael offered Reagan the opportunity to connect Black Power and campus activism. "We cannot have the university ... used as a base to foment riots from," retorted Reagan. The candidate pitched his appeal almost exclusively to white voters, rarely stopping in African American communities or addressing black audiences. (my emphasis)

The whiny white folks phenemenon, in other words, California version. And the "hippies" were a big symbol of what they were whining about. And since hippies were a new, diffuse movement, it was more respectable to describe them as smelly monkeys than to apply such terms to other feared groups. In this sense, "hippies" functioned a bit like George Allen intended "macaca" to function during his Senate campaign this past year.

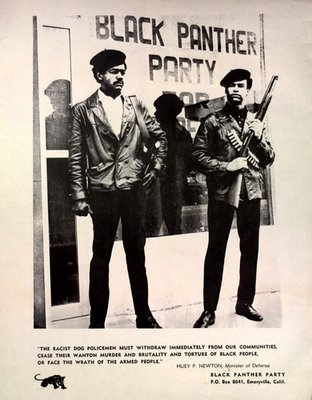

The Second Amendment in action? Black Panther Party poster, 1968; the caption says, "The racist dog policemen must withdraw immediately from our communities, cease their wanton murder and brutality and torture of black people, or face the wrath of the armed people".

The Second Amendment in action? Black Panther Party poster, 1968; the caption says, "The racist dog policemen must withdraw immediately from our communities, cease their wanton murder and brutality and torture of black people, or face the wrath of the armed people".Why people who think of themselves as responsible citizens so often fell the need to have people to sneer at to illustrate their own alleged superiority is still kind of a mystery to me. But those good Republican white folks who learned to sneer at "hippies" and other undesirables in the 1960s and early 1970s kept many of those attitudes alive so that they are now dominate in today's authoritarian Republican Party.

A few good words for the hippies

Herbert Marcuse, one of the more famous names among what was called the New Left in the days of the hippies, actually appreciated the phenomenon as a manifestation of more-or-less instinctive protest against a number of bad aspects of what was then often called "the affluent society" after the title of John Kenneth Galbraith's famous book. (Reagan tried unsuccessfully to get Marcuse fired from a teaching post in the University of California system.)

He addressed the hippie movement in a lecture of July 1967 called, The End of Utopia. For this quotation, unless you just happen to like pouring through Hegelian philosophical essays, just take a deep breath and go with the flow:

We already know what cybernetics and computers can contribute to the total control of human existence. The new needs, which are really the determinate negation of existing needs, first make their appearance as the negation of the needs that sustain the present system of domination and the negation of the values on which they are based: for example, the negation of the need for the struggle for existence (the latter is supposedly necessary and all the ideas or fantasies that speak of the possible abolition of the struggle for existence thereby contradict the supposedly natural and social conditions of human existence); the negation of the need to earn one's living; the negation of the performance principle, of competition; the negation of the need for wasteful, ruinous productivity, which is inseparably bound up with destruction; and the negation of the vital need for deceitful repression of the instincts. These needs would be negated in the vital biological need for peace, which today is not a vital need of the majority, the need for calm, the need to be alone, with oneself or with others whom one has chosen oneself, the need for the beautiful, the need for "undeserved" happiness - all this not simply in the form of individual needs but as a social productive force, as social needs that can be activated through the direction and disposition of productive forces.To boil it down a bit, Marcuse, who was one of the legenary Frankfurt School, approached social criticism with a utopian Marxist perspective. So when used the term "negation", he meant it in the Hegelian sense of "preserved, cancelled and lifted up to a higher level of development". He argued that in the advanced capitalist countries, the possibilities of technology made it immediately feasible to reduce the amount of work required to support the basic needs of the people and also eliminate poverty.

Herbert Marcuse

Herbert MarcuseHe saw the hippies' rejection of conventional jobs and career paths as an expression of that recognition. He also saw them challenging aspects of the established society such as the arms race and destructive competition. Marcuse also argued on Freudian grounds that the level of "instinctual repression" that was required to maintain the existing pattern of social relations also built up a tremendous amount of aggression among people that was manifested in various destructive ways, not least of which was international war.

Unwind the philosophical terminology, and that's basically what he's saying there.

In response to a question after the lecture, he said:

... I am supposed to have asserted that what we in America call hippies and you [in Germany] call Gammler, beatniks, are the new revolutionary class. Far be it from me to assert such a thing. What I was trying to show was that in fact today there are tendencies in society - anarchically unorganized, spontaneous tendencies -that herald a total break with the dominant needs of repressive society. The groups you have mentioned are characteristic of a state of disintegration within the system, which as a mere phenomenon has no revolutionary force whatsoever but which perhaps at some time will be able to play it role in connection with other, much stronger objective forces.Again unwinding the philosophical language, he is saying there that such countercultural movements as the hippies do not, contrary to the paranoia of those we today call "culture warriors", did not have the capacity to make fundamental changes in the power relationships of American or German society. They were unorganized, largely nonpolitical groups who were finding new ways to live and raising important challenges to some of the ideas and practices of the dominant society.

Marcuse was very well aware of the ability of capitalist societies to "co-opt" dissenting movements, to tame them so that they became nonthreatening. But I don't believe he meant that response just quoted to be dismissive of the hippies. On the contrary, he credited them with identifying problems in society that were actually tional-minded (including more traditionally-minded Marxists) were recognizing.

For a couple of online looks at the hippie movement, see A Most Merry and Illustrated History of The Hippies and The Psychedelic 60s

No comments:

Post a Comment