The piece struck me as largely superficial, the kind of thing that one would have found at the time in standard and generally superficial coverage in the mainstream press about the hippie scene and the "youth movement." Someone would describe the author later in life as "an intellectual dilettante"; more on that below.

But the one thing that struck me as something more enduring was this:

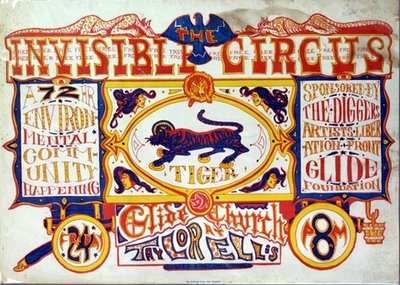

The development of the Beatles and the entire popular-music field in the past few years is reminiscent of the 1909-14 era, when an entire artistic generation rose to heights that have not since been equaled; yet there is a great difference, for Stein, Joyce, Picasso, Matisse, and Schönberg were speaking to an extremely small audience: the pop people are directing their statements to the entire world. The increasingly critical attitude of this new elite with respect to the older generation, and their ability to dramatize their feelings, are rapidly changing the consciousness of an entire generation.Now even this sounds like advertising copy for an art exhibit. But there is something to be said for the ways in which popular music in the 1960s played a particularly important role in popularizing new ideas and other lifestyles. The Beatles' St. Pepper's Lonely Heart's Club Band album, for instance, included an old-fashioned pop song, "When I'm Sixty-Four"; "Within You Without You," musically and thematically heavily influenced by Indian music and Hindu understanding of life; and the very contemporary "Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds," which reflected a psychedelic imagination, whether or not the title actually was a play on LSD.

Other parts were much less substantial than even that. For instance:

The psychedelics are new forms of energy, whose use will depend upon the situation in which they occur - hence the careful planning of the research worker interested in investigating a few linear parameters: a deep contrast to the teenager who downs 500 ug of LSD and goes out to a rock concert. One has expectations of particular results; the other wishes to experience new structures. One activity is based on a linear model the expansion and improvement of an old form, the energy being directed to maintaining the old game; the other activity opens up the individual to manifold experiences which will allow him to create a new game.Apart from the likelihood that the kid will take damaging doses of LSD and/or something else, it seems more plausible to assume that most teenagers doing that would mainly have been looking for entertainment, rather than "manifold experiences which will allow him to create a new game." Actually, the more serious LSD researchers would seem to have been more likely to have "a new game" in mind.

There's this notably Reagan-esque comment: "California is quickly becoming overpopulated

and over-extended financially - the paradise has a serpent lurking in the garden." Say what?!

This also jumped out at me:

We can see the same progression in the psychoanalytic world as it moved from individual therapy to group therapy to marathon (twenty-four-to-thirty-six hour sessions) to a situation similar to that of Synanon, wherein the encounter goes on continuously, twenty-four hours a day, until the individual is converted - Wagner's idea of the Gesamtkunst functioning within a totally controlled environment (Bayreuth) that allows for the experience of conversion. We live in the age of the true believer.He seems to be confusing psychoanalysis with psychotherapy more generally.

And Synanon was a cult, a relatively nasty one even in the cult world. But the author pretty clearly sees it as the cutting edge of a desirable development. Even though even by his description, it sounds like a particularly demanding cult.

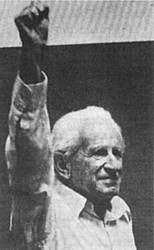

I wish I had written down by comments on the article before I did an online search to see what the author, Ira Einhorn, had been up to since 1970: Ex-Fugitive Convicted in 25-Year-Old Murder New York Times 10/18/2002:

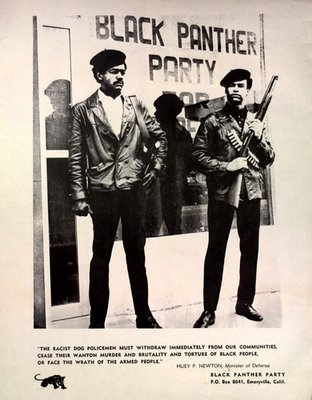

Ira Einhorn, a former counterculture leader who preached peace and love while battering his lovers, was convicted today of first-degree murder for killing a former girlfriend in 1977 and stuffing her body into his closet.See also: Joseph Geringer, Ira Einhorn: The Unicorn Killer TruTV.com (n.d,, 08/25/2011?).

Mr. Einhorn, who fled the country and spent nearly 17 years in Europe after being arrested in the death of Holly Maddux, was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

After the verdict, Judge William J. Mazzola called Mr. Einhorn, 62, "an intellectual dilettante who preyed on the uninitiated, uninformed, unsuspecting and inexperienced."

Rightwing shrieker Michelle Malkin tried to use the fact that Einhorn was involved in some way with the original Earth Day to slam a later version of the event.

Actually, I did read the original article before I searched for information on his later life. I didn't see anything in the 1970 article that indicated to me he was on track to become a violent criminal. But the original piece does read like hype cobbled together from then currently fashionable notions among the hippie subculture. But most people who write superficial tripe don't murder their ex-girlfriends and hide their bodies in a trunk in the closet for weeks.

Tags: hippies, psychedelics, sixties