|

| Rightwing propaganda representation of the "stab-in-the-back" |

Bremm describes the theory this way:

In der langen Geschichte der Schlachten und Feldzüge war es ein nahezu beispielloser Vorgang. Eine Nation, die für ihre militärischen Qualitäten bis dahin weltweit respektiert oder gefürchtet war und deren Armeen sich im Oktober 1918 noch an allen Fronten tief im Feindesland behauptet hatten, warf im November 1918 unvermittelt und entnervt die Waffen fort. Die erst drei Tage alte Republik ließ ihre unglückseligen Vertreter hastig karthagische Waffenstillstandsbedingungen unterzeichnen, die den fluchtartigen Rückzug der scheinbar noch unbesiegten Divisionen des Heeres hinter den Rhein diktierten.This is a ridiculous conclusion, at least formulated in the way Bremm does.

Trotz der allgemeinen Erleichterung über das so unvermittelt eingetretene Ende des deutschen Widerstandes rieben sich die alliierten Führer verwundert die Augen. ...

Plötzlich waren die Enttäuschung und vor allem die Scham über die vorzeitige Kapitulation grenzenlos. Dazu traf die Besiegten der internationale Spott: „Bevor sie am eigenen Leib das Leiden und die Zerstörungen des Krieges erdulden mussten, hätten sich die Deutschen vorteilhaft aus der blutigen Affäre gezogen, in die doch sie allein die Welt gestoßen hatten", höhnte der französische Schriftsteller Henry Lichtenberger und der britische Journalist George Young bemerkte einigermaßen verständnislos: Es wäre besser für die Deutschen gewesen, wenn sie mehr Mut bewiesen und weniger schnell aufgegeben hatten.

[In the long history of battles and military campaigns, it was a nearly unprecedented instance. A nation that until then was respected or feared worldwide for its military qualities and which in October 1918 had still maintained its armies deep in enemy territory, in November 1918 directly and unnerved threw their weapons away. The only three days old Republic had its unlucky representatives hastily sign a Carthaginian ceasefire that dictated the hasty withdrawal of the apparently still undefeated divisions of the army behind the Rhine.

Despite the general relief over such an immediately arriving end of the the German resistance, the Allied leaders rubbed their eyes in wonder. ...

Suddenly the disappointment and above all the shame over the premature capitulation were boundless. International mockery about that was directed at the defeated {Germans}: "Before they had to tolerate the sorrows and destructions of the war in their own body, the German advantageously pulled them out of the bloody affairs, into which they alone had thrust the world." {my translation from the German}, taunted the French writer Henry Lichtenberger. And the British journalist George Young remarked fairly unsympathetically: It would have been better for the Germans if they had shown more guts and not given up so quickly.] [my emphasis]

As Lothar Machtan, biographer of the Kaiser's last Chancellor Max von Baden, puts it in "Autobiografie als geschichtspolitische Waffe" Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 4/2013, by October 1918 Imperial Germany had become "ein politisches System und einen Herrscherstand retten ... die nur durch eine veritable Neuerfindung hätten überleben können" ("a political system and a governing elite ... that could have survived only through a veritable reinvention [of itself']").

|

| "Your |

The Kaiser and his generals had failed across the board. They launched a war of aggression under the false pretense of a defensive war. They denied concealed the consistently expansionist goals to which they held until military failure eventually forced them to recognize their impossibility of achievement, as Fritz Fischer famously documented in detail in Griff nach der Weltmacht (1961).

Gerd Krumeich in his article on the Dolchstoßlegende in the Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg (Gerhard Hirschfeld et al, Hrsg; 2009) notes:

[Gen. Wilhelm] Groener, [Gen. Hermann von] Kuhl und sogar [Gen. Paul von] Hindenburg hatten betont, daß das deutsche Heer im Spätherbst 1918 keineswegs mehr an »allen Fronten siegte« und daß es sich seit den militärischen Katastrophen des Juli/Aug. 1918 nur noch darum habe handeln konnen, einen »anständigen Frieden« zu erreichen - was indessen durch die revolutionäre Entwicklung unmoglich geworden sei.In other words, well over a year before the end of the war the Kaiser's glorious generals were whining that the civilians on the home front had failed to be worthy of their glorious generalship, the generalship that had grossly overestimate their own capabilities and failed repeatedly to deliver the results they promised to the nation. The leadership that had expected what became the nearly 4 1/2 year carnage of the First World War to be a short war of a few weeks ending in German victory with vastly expanded territory and even more vastly expanded effective control over neighboring nations and new colonies.

[{Gen. Wilhelm} Groener, {Gen. Hermann von} Kuhl and even {Gen. Paul von} Hindenburg had emphasized that the German army in late autumn 1918 had certainly not "won on all fronts" and that since the military catastrophe of July/August 1918 the only option was to work to achieve an "respectable peace" - which, however the revolutionary development made impossible.]

An in October 1918, they knew they were beaten. And Gen. Erich Ludendorff, who had functioned in effect as a military dictator since mid-1917, was happy to turn over his disastrous loss to the Social Democrats to let them take the heat for the defeat and what turned out to be a humiliating peace. They didn't even try to "reinvent" the Imperial Government. It was finished.

There is a lot to criticize about the politics of the Social Democratic Party and its leaders Friedrich Ebert and Philipp Scheidemann during their first few months in office.

But their initial agreement to a ceasefire that represented a non-annexationist peace and recognized the cold reality of the failure of the Kaiser and his generals in their war, was the only sensible option open to the new government. In fact, if the leaders of the Entente Powers had shown more judgment and restraint in the peace negotiations than greed and the general spirit of banditry that they did - leading the ineffectual Woodrow Wilson by the nose along with them - they would have imposed far fewer punitive conditions than they did on Germany.

But the bullheadedness and stupidity of David Lloyd George and Georges Clemenceau and the fecklessness of Wilson at the Paris Conference that produced the travesty known as the Treaty of Versailles is not in itself an indictment of new German government to accept the ceasefire terms. (A "Carthaginian" ceasefire? Please.)

For all the faults of the political policies of the Majority SPD of Ebert and Scheidemann during the war, they were consistent in demanding a non-annexationist peace. Keeping a defeated army in the field fighting even longer would have resulted in far more deaths and destruction to the German Army. War is war, so it's no surprised that there were jingoistic-minded Brits and Frenchmen like those Bremm cites would would have preferred to see the German Army further chopped up on the field, even if that meant many more of their own fellow Brits and French killed. War makes people do and say stupid things.

But for Bremm to take those as some kind of meaningful indictment of the new German government's policy on the ceasefire is just plain silly.

It's worth noting, too, that the previous year the Kerenski government in Russia that took power in the February 1917 revolution also made the fateful decision to continue their war against Germany. It didn't work out well for them. Ebert and Philipp Scheidemann weren't fools enough to ignore that experience, either!

As Machtan writes:

Von Anfang an blies ihnen überdies ein eisiger Wind aggressiver Ablehnung durch diejenigen Kreise entgegen, die die deutsche Kapitulation und die deutsche Revolution für ein Versagen der Verantwortlichen, ja für ein Verbrechen hielten und nicht müde wurden, die vermeintlich Schuldigen schonungslos an den Pranger zu stellen. Das provozierte jenen fatalen ideologischen Bürgerkrieg, der wesentlich zur Zerstörung der Weimarer Republik beitrug.This was a circular process. The Kaiser and his generals failed in their plan to snatch territory, colonies and power from their neighbors on the basis of which they launched the war in 1914. As Bremm himself describes at some length, the German generals had constantly declared victories, hidden their failures and systematically presented a sanitized version of the reality of the war to the home front. When they could no longer hide their ultimate failure, they turned the collapsing mess over to the Social Democrats so they cold take the blame for the failure. Then they and their allies in the nationalist movement proceeded to loudly blame the Social Democrats (and the Bolsheviks and the Jews) for their own failures.

[From the beginning on, an icy wind of aggressive rejection blew against them from those circles who held the German capitulation and the German revolution to be a failure of the responsible official, and even a crime, and who never tired of ruthlessly pillorying the alleged guilty ones. Which provoked that fatal ideological civil war that contributed in an essential way to the destruction of the Weimar Republic.]

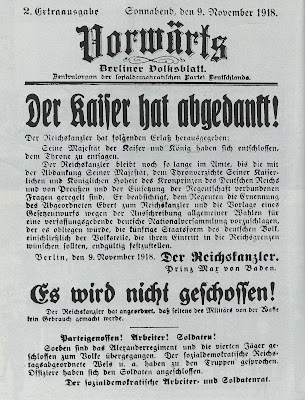

|

| "The Kaiser has abdicated!" SPD special edition cover |

Gerd Krumeich also writes of the roots of the stab-in-the-back myth:

So ist beispielsweise bereits der mangelnde Nachschub in den Kämpfen um Verdun im Jahre 1916 in der soldatischen Literatur als »Dolchstoß« bezeichnet worden. Bereits im Juli 1917 formulierte General von Seeckt den archetypischen Vorwurf: »Wozu fechten wir noch? Die Heimat ist uns in den Rücken gefallen, und damit ist der Sieg verloren«. Durch Streikaktivitäten und Anti-Kriegsagitation, z. B. des Spartakusbundes im Frühjahr 1918, wurde dieser Vorwurf zunehmend nachdrücklicher. Auch die Tatsache, daß den heimkehrenden Soldaten ab Nov. 1918 immer wieder in öffentlicher Rede bestatigt wurde, sie seien »im Felde unbesiegt« geblieben, festigte vielfach die Uberzeugung, daß die Niederlage nicht militärische Gründe gehabt hatte, sondern von »den Zivilisten«, »den Arbeitern«, »den Juden« usw. zu verantworten sei.In other words, this idea was constructed by the military as a fallback alibi long before the end. We've seen this in other situations, as well. The US military promoted a very similar claim about the Vietnam War.

[So, for example, the shortage of reinforcements in the battles around Verdun in the year 1916 already had been labeled in the soldiers' literature as a "stab-in-the-back." Already in July 1917 General von Seeckt formulatede the archetypical accusation: "What are we still fighting for? The homeland has attacked us from behind and therefore the victory is lost." By strike activities and antiwar agitation, for example that of the Spartacus League early in the year 1918, this accusation became more and more insistent. Also the fact that the returning soldiers starting November 1918 continually claimed in public speeches that they remained "undefeated in the field," reinforced many time over the conviction that the defeat didn't have military grounds, but rather than "the civilians," "the workers," "the Jews," and so forth were responsible.]

Bremm even cites Von Seeckt's 1917 whining, but cites it as though it were a statement of the obvious rather than an ideological and political construction.

And, as as the undated article Die "Dolchstoßlegende" from the SPD Ortsverein Feldmoching-Hasselbergl puts it, "Hindenburg und Ludendorff hatten nach der gescheiterten Sommeroffensive von 1918 die Reichsregierung am 29. September 1918 ultimativ aufgefordert, Waffenstillstandsverhandlungen aufzunehmen." ("Hindenburg and Ludendorff after the failed summer offensive of 1918 demanded in an ultimative way that the Imperial government start ceasefire negotiations.") Kaiser Bill (Wilhelm II) abdicated on November 9. The same day, the Kaiser's last Chancellor Max von Baden turned over the government to Friedrich Ebert and his Social Democrats.

|

| Cover of a book on the Dolchstoß Trial |

Both Bremm and Krumeich refer to the Munich Dolchstoß Trial of October-November 1925, in which an editor was sued for by the head of a conservative publication over the latter's accusing the Social Democrats of having performed a stab-in-the-back in the First World War. (This sides are a bit confusing: Martin Gruber of the Münchener Post had accused Paul Nikolaus Cossmann of the conservative of spreading poisonous propaganda by promoting the stab-in-the-back myth, and Cossman sued Gruber over the criticism; it was the conservative side that initiated the suit.) The court found narrowly that the SPD could not be accurately accused of such a thing, but nevertheless reinforced the idea that the stab-in-the-back had taken place. Krumeich:

Das Ergebnis des Prozesses war, daß die Mehrheitssozialdemokratie der Kriegszeit vom Vorwurf entlastet wurde, sich am »Dolchstoß« beteiligt zu haben. Es bestand aber für das Gericht kein Zweifel daran, daß erhebliche Versuche unternommen worden waren, die Front zu destabilisieren.Bremm's description of the Dolchstoß Trial runs like this:

[The result of the trial was that the Majority Social Democracy of the time of the war was acquitted of the accusation that they had taken part in the stab-in-the-back. But there remained for the court no doubt that significant attempts had been undertake to destabilize the front.] [my emphasis]

Im Münchener „Dolchstoß-Prozess", den der Publizist und zum Katholizismus konvertierte Jude Paul Nikolaus Cossmann im Oktober 1915 unter großer offentlicher Aufmerksamkeit gegen den leitenden Redakteur der Münchener Post wegen Verleumdung angestrengt hatte, bestand selbst fur das Gericht bei aller Abwagung der bekannten Fakten kein Zweifel, dass im zurückliegenden Krieg erhebliche Anstrengungen in der Heimat unternommen worden waren, die deutsche Front zu destabilisieren. Wenn auch die hauptsachlich attackierte Sozialdemokratie vom Vorwurf, dem Heer in den Rücken gefallen zu sein, durch das Verfahren insgesamt entlastet wurde, war damit doch der Dolchstoß-Topos nun auch gerichtsnotorisch.Bremm cites a separate 2002 article by Gerd Krumeich at the end of that paragraph. But Krumeich's description in the 2009 article cited above not only frames it notably differently, he explicitly describes the partisan nature and repercussions of the court's decision endorsing the idea of the stab-in-the-back myth: the decision "schuf insgesamt eine eindeutig parteipolitische Ausrichtung der Frage nach den Gründen des deutschen Zusammenbruchs von 1918" ("altogether created a clear party-political bias to the question of the reasons for the German collapse of 1918.")

[In the Munich "Dolchstoß Trial" which Paul Nikolaus Cossmann, a publicist and a Jew who had converted to Catholicism brought in October 1915 under great public attention against the chief editor of the Münchener Post on the grounds of defamation, there remained for the court after all consideration of the known facts no doubt that in the previous war substantive efforts had been undertaken on the homefront to destabilize the German front. Even though the Social Democrats, who were the main ones accused {in the case of the stab-in-the-back}, were acquitted on the whole of the accusation of having attacked the Army from behind, the stab-in-the-back theme was thereby also given judicial notoreity.] [my emphasis]

"The trial," as the SPD Ortsverein Feldmoching-Hasselbergl article puts it, "was a pure conservative propaganda maneuver" ("Der Prozeß war eine reines konservatives Propagandamanöver").

Bremm presents it rather as producing a judicial verification of the stab-in-the-back claims.

To say it again, this is a ridiculous conclusion on Bremm's part.

Tags: dolchstoßlegende, first world war, erster weltkrieg, stab-in-the-back, world war i

No comments:

Post a Comment