|

| Jean Jaurès (1859-1914) |

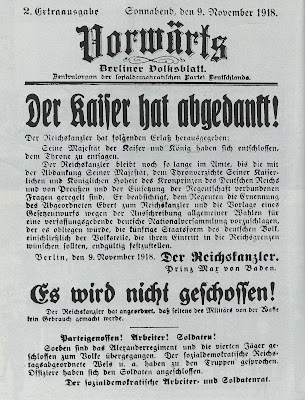

A warmongering French nationalist thug named Raoul Villain murdered him on July 14, 1914, just days before the decadent rulers of Europe plunged themselves in a massive and completely unnecessary war that turned out to be the most destructive in history. Until the next world war. At the end of the slaughter, four long-standing imperial dynasties had fallen: The German Hohenzollerns of "Kaiser Bill"; the Habsburgs of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, then destroyed forever; and the rulers of the Ottoman Empire, also destroyed forever.

Sam Ball describes Jaurès' anti war position (France remembers murdered socialist hero Jean Jaurès France 24 07/31/2014):

In 1902, Jaurès became one of the founding members and leader of the French Socialist Party, later the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) – the forerunner to today’s Socialist Party of current President François Hollande. He also founded the socialist paper L'Humanité, still going today, whose editors he was having dinner with at the time of his murder. ...Despite Jaurès' antiwar radicalism, George Mosse once described him as "a very moderate Socialist hero." (Confronting History: A Memoir; 2000; p. 160)

But he is perhaps best remembered, by socialists and non-socialists alike, for his anti-militarism and attempts to avert the outbreak of the First World War.

“Never, for forty years, has Europe been in a more threatening and more tragic situation," he warned in the spring of 1914.

Jaurès spent much of the final years of his life travelling across Europe, attempting to organise general strikes among the workers of the continent’s great powers in order to force their governments to back down from the brink of war.

Henry Ehrmann wrote of the effect of Jaurès' assassination (Jean Jaurès-Last of the Great Tribunes Social Research 16-3 1949)

Jaurès was shot by a nationalist fanatic on the eve of the first world war. In the midst of the clamor of general mobilization a grieved hush fell over all of France. Those who spoke at Jaurès' open grave expressed feeling-s akin to Nehru's brokenvoiced, "The light has gone out of our lives," after the Mahatma's assassination. A British newspaper referred to the event as an international catastrophe; Anatole France and Romain Rolland were confident that after the war Jaurèsian thought would be a source of inspiration throughout Europe and that Jaurès would be recognized as the most representative figure of his age and his country. Official immortalization followed in 1924 with the transfer of Jaurès' ashes to the Pantheon, the Jacobin temple to la patrie.Jaurès' inclusion in the French Pantheon did not impress a young corporal who served in in the German Army during the World War. He subsequently alluded to it (apparently, he didn't specify Jaurès) in the first volume of Mein Kampf, "der Vorderaufstieg in das Pantheon der Geschichte ist nicht für Schleicher da, sondern für Helden!" In the James Murphy translation, "the steps that lead to the portals of the Pantheon of History ... are not meant for place-hunters but for men of noble character." It's a problem of English translations of Mein Kampf that the translator is tempted to make it accessible by softening the gutter rightwing tone of the original. I would translate that, "entry into the Pantheon of History is not for skulkers but for heroes!"

Despite the revolutionary implications of Jaurès' antiwar position, in which he called for “insurrection rather than war" (See below), he was actually the advocate of a more moderate version of socialism than that of the French Marxism of the 1870s.

It would be easy to conflate the antiwar factions in the Second International parties with the more revolutionary faction and the prowar faction with that of the reformist "revisionists." But that would be an oversimplification of the reality. Eduard Bernstein, the godfather of Revisionism in German Social Democracy, became part of the antiwar faction during the First World War, alongside big names of the revolutionary faction like Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, while Bernstein's great opposite number in the Marxism-Revisionism debate, Karl Kautsky, wound up in the prowar faction.

Margaret MacMillan cites Jaurès as someone who was aware of the potentially dangers of what a heading in this Brookings article calls "the complacencies of peace, The Rhyme of History: Lessons of the Great War 12/14/2013:

In short, we have grown accustomed to peace as the normal state of affairs. We expect that the international community will deal with conflicts when they arise, and that they will be short-lived and easily containable. But this is not necessarily true. The Socialist leader Jean Jaurès, a man of great wisdom who tried unsuccessfully to staunch the rise of militarism in France in the early years of the 20th century, understood this very well. “Europe has been afflicted by so many crises for so many years,” he said on the eve of World War I, and “it has been put dangerously to the test so many times without war breaking out, that it has almost ceased to believe in the threat and is watching the further development of the interminable Balkan conflict with decreased attention and reduced disquiet.” [my emphasis]In his signed article on Jaurès in Britannica Online, Claude Harmel writes:

He fought the supremacy of the German Social Democratic Party in the Second International and, in order to deprive it of its revolutionary reputation, confronted it at the Congress of Stuttgart in 1907 with his formula “insurrection rather than war.” This statement, though, did not completely summarize the whole of his political thought; he strove for the adoption of a system that would ensure “peace through arbitration” and recommended a prudent policy of “limitation of conflicts.” He therefore opposed colonial expansion, such as the French invasion of Morocco, because it provided a source of international conflicts.Of course, there is no small amount of tragedy in Jaurès' opposition to war. He believed that with effective democracy, the power of democratic public opinion would be an effective check on war. As sound as that belief was and is, things were not that simple. John Kenneth Galbraith, certainly no warmonger, wrote in The Culture of Contentment (1992):

Hostile to the Franco-Russian alliance and suspicious of the Franco-British alliance because it seemed to be directed solely against Germany, Jaurès became the champion of Franco-German rapprochement; as Germany was France’s traditional enemy, his position earned him the hatred of French nationalists. His passion for reconciliation ultimately led to his tragic death. Up to the last moment, however, he was actively exhorting the European governments to avert a world war and to settle peacefully the conflict that followed the archduke Ferdinand’s assassination at Sarajevo in June 1914. On the very day of his own assassination, Jaurès was considering an appeal to President Woodrow Wilson of the United States for help in solving this crisis. [internal links omitted]

Almost any military venture receives strong popular approval in the short run; the citizenry rallies to the flag and to the forces engaged in combat. The strategy and technology of the new war evoke admiration and applause. This reaction is related not to economics or politics but more deeply to anthropology. As in ancient times, when the drums sound in the distant forest, there is an assured tribal response. It is the rallying beat of the drums, not the virtue of the cause, that is the vital mobilizing force.And once the war gets rolling, it becomes very hard for either side to back off without a clear-cut victory.

The socialists of Jaurès' day also had historical reasons for pessimism over the passion of ordinary people for peace above national glory. Galbraith wrote in an earlier work, The Age on Uncertainty (1977):

In 1870, [Prussian Chancellor Otto von] Bismarck, who had once made overtures to [Karl] Marx to put his pen at the service of his fatherland, went to war with Napoleon III. In a prelude to the vastly greater drama of August 1914, the proletarians of the two countries showed themselves far from being denationalized; instead they rallied to the defense, as they saw it, of their respective homelands. Then, as later, nothing was so easy as to persuade the people of one country, workers included, of the wicked and aggressive intentions of those of another. The First International, already split by disputes, was outlawed by Bismarck and soon by the Third Republic. Its headquarters was moved to Philadelphia, not a place of seething class consciousness; there, a few years later, it expired. In 1889, as a union of workingclass political parties and trade unions, it rose again - the Second International. This Marx did not live to see.The book was a companion volume to a TV documentary series of the same year. The related episode is The Age of Uncertainty Episode 3 Karl Marx The Massive Dissent:

[my emphasis]

Still, the insight that Jean Jaurès and other peace advocates of his time shared is still relevant: the fact that the Other Side has nefarious goals doesn't mean that Our Side's goals are any more noble or worthy. Especially when it comes to policies that lead to the mass killing in war.

Galbraith also notes in the 1977 quote, continuing immediately after the above:

But if the war was the nail in the coffin of the First International, it also gave Marx a moment of hope. For where revolution is concerned, war in modern times has worked with double effect. It has been extremely efficient for mobilizing the proletarians of the world into opposing armies, defeating the dream of the internationally unified working class for which Marx (and those to follow) hoped. But it has been equally efficient for discrediting, at least temporarily, the ruling classes that conducted it - a tendency by no means confined to the countries suffering defeat. [my emphasis]